By Zachary S. Kester, Executive Director and Robert Miller, Program Officer, Charitable Allies

Savvy businesspeople know that the best way to protect personal interests from liability is through incorporating their for-profit business. Incorporating offers many of the same protections for nonprofit organizations. However, errors and omissions of the Board of Directors (“Board”) or Officers can still leave a risk of liability to both the nonprofit and its individual Directors, or Officers. Nonprofit Directors are passionate about causes and serving the community, but they often lack the required knowledge to understand their obligations under the law. Such Directors are doing a good deed by volunteering to sit on the Board; but the consequences of inattention can “punish” their otherwise “good deeds.” If you’re looking to avoid board liability, read on.

Understanding Board Responsibilities

The Directors failure to fully understand the law and risks associated with failing to act in accordance with their responsibilities as a Director could leave the nonprofit and its Directors open to liability.

Directors of nonprofit corporations are fiduciaries, meaning they hold positions that require trust, confidence, the and exercise of good faith and candor. They also have a duty to act for the benefit of others in connection with their undertakings for the nonprofit organization. Specifically, Directors can be held personally liable based on three fiduciary duties: the duty of care, the duty of loyalty, and the duty of obedience. Unfortunately, many board members seem to be unaware of their fiduciary responsibilities for the organization for which they volunteer. Fortunately, however, Directors can only be held responsible for breaches of fiduciary duties if the breach is due to recklessness or willful misconduct.

The Duty of Care

The duty of care requires a Director to exercise the same care that an ordinary, prudent person would exercise under similar circumstances. Generally, this duty is also understood to include informed decision-making and attentiveness. Informed decision-making means knowing the law and the corresponding requirements for the nonprofit organization, keeping tabs on its daily activities, and then, basing decisions on that knowledge. Devoting the necessary attention to the organization requires the Directors to act in a competent manner and spend the time required to care for the organization as needed.

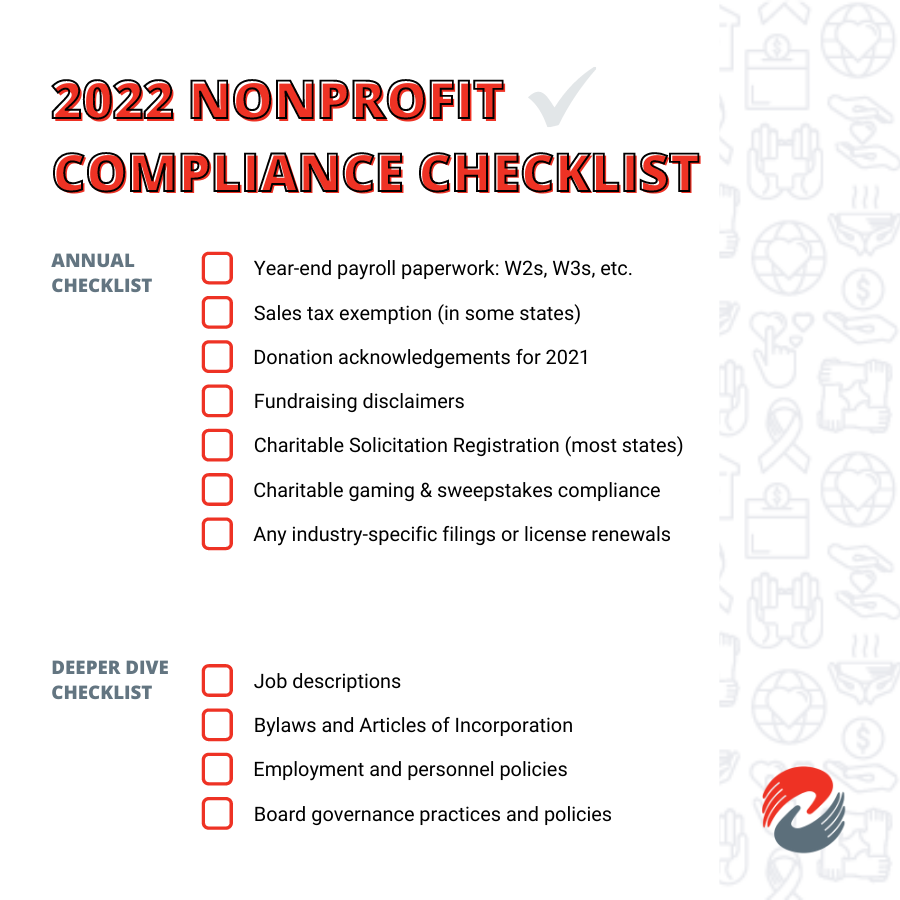

One major way that the duty of care is violated is by the Board’s failure to keep all of the nonprofit’s documents, i.e. the articles of incorporation/organization and the bylaws, updated and current. This means that the Board must ensure that it is regularly reviewing the articles and bylaws and updating them as necessary to keep up with the current workings of the organization.

The biggest trap for duty of care violations though, often relates to employment practices. Of the nonprofit organizations who filed a claim on their D&O insurance in the last 10 years, over 85 percent of those claims were employment related, and some sources estimate it to be even as high as 94 percent!

The Duty of Loyalty

The duty of loyalty requires Directors to act in good faith and pursue an organization’s best interests. This includes full disclosure of any issues that could cause, or be perceived to cause, a conflict of interest and recusing oneself from all discussions, both formal and informal, related to such conflict. It also requires Directors not to take opportunities away from the nonprofit for their own personal gain and to protect the organization’s confidential information.

The biggest issue with this duty is conflict of interest transactions. However, that does not mean that a Director is in violation of this duty when they act in a way that benefits themselves so long as it also appropriately benefits the nonprofit. Additionally, a breach of this duty in this way can be avoided by showing approval of a majority of the disinterested Directors or showing that the transaction was inherently fair.

The Duty of Obedience

Lastly, the duty of obedience forbids acts outside the scope of the organization’s rules, policies, mission statement, articles of incorporation, and bylaws. In addition, the Board must comply with state and federal laws. Directors are supposed to follow the rules of the organization as laid out in the various corporate documents as well as the state and federal laws applicable, but sometimes that is easier said than done. In part this is due to the sheer number and complicated nature of the potential applicable rules, a few of which are discussed in more detail below.

One major issue with the duty of obedience is ensuring that the funds of the nonprofit are used to fulfill the organization’s stated mission, which can include paying rent, employees’ salaries, or executing the program to serve the community. If they are not used in that way, then there is a risk that the nonprofit might lose its tax-exempt status.

Another common issue is the Board’s failure to abide by its own articles or bylaws. Directors must be sure to become familiar with the rules of the organization itself and follow them whenever applicable. Failing to follow the articles or bylaws of the organization can lead to consequences for the organization itself and its board members.

There are two specific laws with which most Directors should be familiar that are described in more detail directly below.

Understanding Board Responsibilities: Volunteer Protection Act of 1997

In addition to the above general fiduciary responsibilities, the Board is also subject to special laws that govern their actions. The Volunteer Protection Act of 1997 (VPA) covers all 501(c)(3) organizations and their volunteers (including uncompensated directors) from liability, unless there is willful or criminal misconduct, gross negligence, or reckless conduct. Where reckless conduct has been described as an intentional act done with reckless disregard of the natural and probable consequence of injury to a known person under the circumstances or, alternatively, as an omission or failure to act when the actor has actual knowledge of the natural and probable consequence of injury and his opportunity to avoid the risk. Notably, the “reckless” standard is the same as in most states’ Nonprofit Corporations Acts.

Even though the Act provides some protection for the nonprofit organizations and their volunteers, it does require Directors to make sure their organization stays compliant with IRS guidelines and maintains its tax-exempt status.

Easily done, right? Yet one of the most common pitfalls for nonprofits is failure to file a Form 990 in a timely manner. That misstep, if occurring for three consecutive years, leads to auto-revocation of a nonprofit organization’s tax-exempt status – and potential loss of protection under the Volunteer Protection Act. Any number of other acts or omission can constitute recklessness as well.

Understanding Board Responsibilities: Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act

Additionally, many nonprofit organizations and their Boards are subject to the UPMIFA, or the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act. The UPMIFA provides guidance on investment decisions and endowment expenditures for nonprofit and charitable organizations.

According to the McGuireWoods Nonprofit & Tax-Exempt Organizations Group, this legislation adds to the standard of care required to be exercised by the Directors when dealing with investment issues. Under this law, nonprofit Directors must consider the whole investment portfolio, the economic circumstances at the time, the organization’s charitable purposes, and the charitable purposes of the fund, if applicable. Additionally, it requires a Board to exercise prudence in cost management by allowing only appropriate and reasonable costs, to investigate the information it uses to make investment decisions, and it requires any Director with special skills or expertise to use such skills or expertise in making investment decisions.

Overall, nonprofit Directors have a number of responsibilities with regards to their fiduciary duties to the nonprofit. These duties include the duties of care, loyalty, and obedience. Additionally, Directors must be cognizant of any special laws and regulations that pertain to nonprofits generally or to nonprofits in their industry specifically, and require them to act in some way to prevent liability.

Minimizing Potential Board Liability

So how can nonprofits properly deal with potential liability issues involving their Board?

Board Member Education

While educating your Directors about their roles and responsibilities, good governance, and any other issues relevant to the Directors along with ensuring to the best of your ability that you choose the right Directors can help a great deal in decreasing personal liability for the Directors. There will however still be a risk that a Director or the Board as a whole will violate one of their fiduciary duties and incur liability. Therefore, it is important to obtain liability insurance to cover those times when violations do occur. But this is not as simple as it sounds.

Liability Insurance

Insurance certainly is a necessary and prudent part of risk management for a nonprofit organization and this includes an appropriately-sized D&O liability policy.

Essentially, there are three types of insurance that nonprofits need to be aware of when making their decision: (1) A-side, which covers claims for direct payments to a director for defense costs and liability damages if directors do not have indemnification rights or indemnification is useless due to financial condition of nonprofit; (2) B-side, which reimburses the nonprofit for indemnity payouts to directors and officers; and (3) C-side, which covers the organization itself for wrongful acts.

However, when choosing policies and insurance carriers, beware of common exclusions that might affect your organization. Common exclusions that we have encountered include: (1) an organization, its Officers, and/or Directors may not make a claim on its own policy (which is unlike auto insurance, for example); (2) employment practices are excluded and generally require a separate rider; (3) exclusions for damages incurred under a written contract (such as breaches of leases or liability for nonpayment of certain creditors where the liability was incurred as a result of a written contract); (4) claims for breached duty of loyalty (i.e., conflict of interest or self-dealing transactions); (5) taxes and penalties; (6) intentional conduct of Directors or Officers; (7) environmental claims; and (8) intellectual property-related damages. Before finalizing your insurance purchase, ask your insurance agent to assess your policy for these exclusions and “plug the holes” for you where possible.

According to Travelers, nearly twice as many D&O claims are made on insurance policies by nonprofit organizations as are made by their public or private counterparts. And in a recent study, up to 63 percent of nonprofit organizations reported a D&O claim in the past 10 years.

Additionally, insurance companies are going to look closely at your Board’s practices before agreeing to cover the organization. Therefore, if your organization’s tax-exempt status has been revoked, the insurance company finds that the Board has not followed best practices and policies in its operation and oversight of the nonprofit, or the organization was less than forthright on its D&O insurance application, then that insurance policy may not be much more than an expensive piece of paper. So, not only is insurance a way to deal with potential Director liability, but it can also be affected by your Directors’ failure to fulfill their responsibilities.

In the end, attaining insurance for your nonprofit is important, but it will not be able solve all of the problems with Director and/or Board liability, especially if the insurance company decides not to pay on the claim. It is important that you and your Board understand all of the responsibilities and duties that a Board has in order to ensure that you comply with them to the best of your ability.

Overall, Director and/or Board liability can be a major issue for nonprofits which might require legal help to resolve, so do not let your good deed be punished by failing to exercise the appropriate care and caution with your nonprofit’s Board in the same way you did with all other aspects of bringing your nonprofit organization to life.

Attorney Zac Kester provides generalist and strategic nonprofit legal and consulting services. He holds a Master of Laws, a post-law school advanced degree, in which he studied the unique needs of tax-exempt nonprofit organizations. His legal and consulting career has focused on nonprofit organizations.

With highly experienced legal and training personnel, Charitable Allies provides all manner of legal and educational services for boards, officers, management and staff of myriad charities throughout the sector. From basic one-time questions about a single matter to training for boards and officers to complex reorganization or merger of activities, Charitable Allies is your go-to cost-effective provider of legal services to nonprofit organizations.

Contact us at 463-229-0229 with questions.